Forget a lot of the blah that today passes off as the definition of good teaching. The present obsession with targets, test results and exam grades is a quaint throwback to a rather old fashioned instrumental model of learning – the student as an empty bottle and the teacher as lab worker who picks up the jug full of knowledge and pours it in.

Like all instrumental models the pattern is flawed because it leaves out one key fact – you are dealing with humans.

Sure test results and exam grades are important as useful indicators of what has been learned but that is not the whole story of what education is about. Schools are also places where children learn how to act as members of a community and a teacher’s job is also to provide them with clues about social conduct. Hence the relationship between teachers and students is an important strand of that learning process.

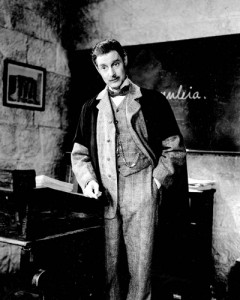

You could call it the chemistry of teaching.

Sometimes it can manifest itself in quite an unusual way.

My first job was in a North London comprehensive school. I lived initially with my parents in Streatham. My daily commute was a bus to Clapham Common Station, the Northern Line to Camden Town then another bus to the school. During the 1960s Northern Line trains were often delayed so sometimes I cut things a little fine and arrived in school just after the bell. It was a big site so by the time I reached my tutor group to mark the register I was running even later. Usually there were still kids milling about the corridors and my delayed appearance did not appear to be noticed.

How naive of me. My card had been marked and the Head himself had decided to confront me at the scene of the crime.

Fate decreed that on the very morning that the Head hovered around our particular corridor I was even later than usual. I slipped in through a side door, dashed up the back stairs and ran into the classroom, got to my desk and opened up the register – and suddenly noticed it had already been marked. I looked up, obviously rather puzzled and one of the girls told me that the Head had come into the room and asked where I was. Immediately the worst case scenario flashed across my mind. The Head had marked the register in my absence and later that morning I would be summoned to his office for a grade A bollocking.

But the kids had obviously read my fearful face.

“It’s OK, sir – we knew you were late so we marked the register for you and told the Head you’d gone down to the history stockroom to fetch a book” said one of them

When later in the day I told Ted G, our Head of House – a grizzled LCC veteran – he just nodded and said “Well Dave, you’ve passed the most important test. Forget about degrees and certificates. The kids might sometimes still try to cause trouble but if they back you up in that sort of situation you have passed their exam with flying colours. In their eyes you are now a proper teacher. But if I were you I’d bloody well make certain I was a proper teacher who arrived on time.”

Good old Ted G. He taught me a lot about stuff that my teacher trainers never mentioned – what he called the chemistry of teaching. I was never late again – I got up earlier and left a margin for delays. I’m also, fifty years later, still in touch with some of those “kids”. I never was a softy or one for thinking that the classroom could be a democracy. But I always believed that young people should be treated with respect – and that working with them was a privilege and I never had cause to regret that belief.